An essay ostensibly arguing that Temple of Doom is the best Indiana Jones movie, but which veers into a larger analysis of the trilogy and the Indiana Jones character

Let’s talk theme. Ideally, a great movie should be about something great, and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom — like Aliens — is a sequel that tops the original, and it tops Raiders of the Lost Ark not because it’s a bigger, grander movie, but because it goes to a dark, scary and different place to explore a worthy theme: parenthood.

Temple of Doom (TOD) and Aliens are also blood cousins in how both introduce a great theme (parenthood) into movie series that, for all their excellence, lacked heart in their first chapters. Ellen Ripley just happened to survive the haunted house/slasher movie that was Alien, and it was James Cameron who had the good sense to turn Ripley into an action-movie-uber-mom — Rambo with a long-lost daughter. Pauline Kael called Raiders of the Lost Ark an “impersonal” movie; a lesser movie sandwiched between two of Spielberg’s greatest works (Close Encounters and E.T.). Now, having cited Kael’s quote as evidence that Raiders is somehow a lesser movie than TOD, I’ll admit that I’m not sure what the hell she was talking about. Perhaps Kael found Spielberg’s loving and exact recreation of the old, swashbuckling, Allen Quatermain-style serials too exact for her taste; too assiduous in its adherence to the images needed to fulfill its pastiche quota. And maybe I’m too taken with the movie’s nonstop ass-kicking to look at it critically enough. Roger Ebert, though, hit on a great point that gives Raiders more heart than Kael gives it credit for. He says Spielberg wants to do two things in Raiders: “make a great entertainment, and stick it to the Nazis.” And I agree, though I still place it below TOD.

(Another 80s action movie classic deserves mention for having a parental theme (this one in spite of its low-brow roots): Commando, starring Arnold Schwarzenegger. In it, Schwarzenegger plays a former Delta Force badass who comes out of retirement to rescue his kidnapped daughter, single-handedly killing more than 100 men along the way and inspiring slack-jawed awe in all the raised-by-women Gen-X sons who saw it. Side note: did you know that Schwarzenegger used to be a world-champion bodybuilder and is now the governor of California?)

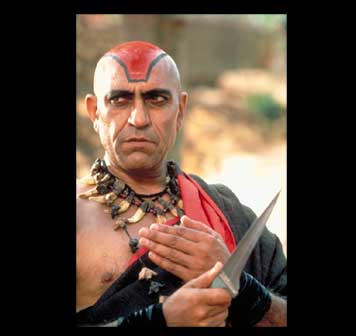

First, a concession: TOD has never been known for its sympathetic portrayals of minorities, what with its wacky Chinese sidekick, leering Chinese gangsters, and crazy Hindu-Indian-Devil-worshipping-human-sacrificers. Indeed, between Mola Ram and his gog-eyed acolytes, the movie does more to sully the image of middle-easterners than a 24-hour marathon of Fox News.

What mitigates these indiscretions somewhat, though, are not only the two movies bracketing TOD — in which the bad guys are the whitest, most evilest motherfuckers this side of Mordor (the Nazis) — but also the strong, well-executed relationship between Indy (Harrison Ford) and Short Round (Ke Huy Quan).

Let commence the radical shift in topic for no apparent reason

But before we analyze Indy’s relationship with Short Round — the chief reason why TOD reigns supreme over Raiders and Last Crusade — let’s break down Indy’s transformation from greedy, skeptical mercenary to museum-friendly man of faith. In doing this, I plan to focus on problems in consistency that arise from the odd chronology of the series (TOD takes place before Raiders) and some flat-out bad writing — most of which is in the third movie, Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

Spiritually, Indy’s character follows a steadier course over the release order of the movies (Raiders, TOD, Last Crusade), so let’s examine the movies in that order first, focusing on Indy’s progression from hard-core atheist to a man of outright religion. In Raiders, Indy treats all matters metaphysical with skeptical kid gloves. When the two government reps ask Indy what’s going on in that freaky illustration of the Ark of the Covenant he shows them, Indy steps away from the table, averts his eyes, shrugs and mumbles (uncomfortably?), “Lightning. Fire. Power of God.” It’s Marcus who tries to freak out the Army guys by taking such pleasure in language like, “Wiped clean, by the wrath of God”; and it’s Marcus (and later Sallah) who honestly gets a little freaked out about actually, literally finding this deadly fucking thing called the Ark. In the first example, when Marcus says that the Ark is like nothing Indy has “ever gone after before,”Indy hits him with one of the great dismissive quips from the canon of atheistic thought: “I’m going after a find of incredible historical significance. You’re talking about the boogeyman” [italics mine].

But Indy, good Biblical scholar that he is, remembers from his Old Testament studies that only a high Jewish priest can look at the Ark (whereupon God, as the story goes, resides). So when the Nazis open it, and freaky, boogeyman-like weirdness starts happening, Indy instantly shuts his eyes and tells Marian to do the same. Whether or not being an aural witness to the divine slaughter of a few dozen Nazis (and the head-detonation of one French Nazi stooge) turns Indy into a believer (I don’t think so), Indy joins Marcus in a joint freak-out over what the Army plans to do with the Ark — they’d rather have it in a concrete bunker than a museum.

On to TOD. Again, I know this movie is set before Raiders, but in many ways it’s still a sequel to Raiders. One superficial example: the callback to the famous scene in Raiders where Indy just shoots the big guy with the big sword. In TOD, Indy encounters two bad guys with big swords, finds that he doesn’t have his gun, and has to kick their asses the old-fashioned way. A great bit, but Indy the atheist also continues to develop in the minds of Spielberg and Lucas. Near the beginning of the movie, when the village mystic — where did they find this guy?! — tells Indy that Shiva made them all fall from the sky, Indy assumes the wide-eyed, patient posture of a parent explaining to their kid that Santa Claus is a myth: “We’re weren’t brought here. Our plane crashed.” Soon after, when Short Round asks Indy if something indeed made their plane crash, Indy once again dismisses it: “No, shorty, it’s just a ghost story, don’t worry about it.”

However, Indy’s large-hearted outrage over the Thugee cult’s enslavement of the village’s children not only drives him to destroy the titular temple and free all the kids, but it also leads Indy to one of his most religious — and patently bizarre — moments in the trilogy. Dangling from a severed rope bridge and fighting for his life against the evil Mola Ram, Indy, who had earlier referred to one of the sacred Sankara stones as a “good luck rock,” starts speaking in tongues. I’d quote his lines here if I could tell what the fuck he was saying (besides “you’ve betrayed Shiva”), but even after more than 50 screenings of this classic, I still can’t decipher the Hindu litany that Indy growls at Mola Ram through tight, pursed lips and accompanied by the flinty, glinty gleam of his eyes. (I still consider this one of Ford’s best moments of pure acting because it’s so damn out there.) Again, as far as Indy’s change from atheist to agnostic (at least), I place this movie after Raiders because in Raiders, Indy only had to acknowledge religion by closing his eyes; here he actually channels it to save the day — and it works! Indy’s chant causes the Sankana stones to glow red-hot and burn through a burlap knapsack. For an atheist, Dr. Jones knows his Hindu mysticism well enough to command the ear of Shiva at the moment of truth.

Ha! Another great moment of religiosity for Indy: When he, right before chopping down an old rope suspension bridge he’s trapped on, says to Mola Ram (with righteous fury), “Mola Ram, prepare to meet Kali in HELL!” (The idea of Hell of course being anathema to any upstanding atheist.) OK, that’s a not a really great example, but that line always cracks me up.

Oh, Indy also has a by-the-numbers religious softie moment with the aforementioned village mystic at the very end when he returns their “good luck rock” and says, “Yes. I understand its power now.” It’s a solidly performed and necessary scene, but it lacks the what-the-fuck quality of the speaking-in-tongues bit.

Incidental side note

Amrish Puri? The guy who plays Mola Ram? That’s dude’s done more than 200 Bollywood musicals. Well, Bollywood movies at least — I’m just assuming they’re all musicals–Jesus! I’m looking at his IMDb listing, and this fucker did eight other movies the same year he did TOD! How is that physically possible?! Don’t Spielberg/Lucas/Indiana Jones classics take, like, a jillion months to shoot?! Fuck, I would think that a jillion-month schedule would be the bare minimum needed to cram the amount of awesomeness that they do into these movies. Did 1984 have a jillion and 12 months in it? Because that’s how much time Puri would have needed to shoot nine fucking movies — one of which was the coolest Indiana Jones movie ever!

There’s only one answer. Amrish Puri is a demigod.

Back to business

Finally, in Last Crusade, we of course get to see the end of this arc. Now, before I tear screenwriter Jeffrey Boam a new asshole for all the cheap summer-movie gags he pukes into his script, let me praise the vast majority of the movie, which he really nails. I’m sure in the planning stages for Last Crusade, Spielberg and Lucas giggled with delight over the idea of hiring Sean Connery, still our best James Bond, to play the father to their own James Bond. (Did you know that they almost used the opening for TOD as the opening for Raiders? Spielberg and Lucas agreed that Indy was their take on the James Bond legend, but decided to save their clearest allusion to Fleming’s super-spy — Indy in a tux — for the second movie. Connery himself said of Indiana Jones, “He’s James Bond, but not as well-dressed.”) But despite the financially motivated, crowd-pleasing reasons behind adding Indy’s father to the mix, the character — wonderfully played by a nebbishy-against-type Connery — adds dramatic heft to an already strong script. Because not only is it great to make Indy deal with his emotionally distant father, it’s even more effective to make Indy the atheist deal with his deeply religious father. (More on that later.)

But even before joining his father on a religious adventure, we see that Indy’s atheism is wavering. After finding out that his father’s gone missing while searching for the Holy Grail, Marcus and Indy go to his father’s house, only to find it ransacked. While searching the mess for clues, Indy takes a good, long, hard look at a painting on his father’s wall: a man walking on air toward the Grail. And in this, the third movie, it’s Indy, not Marcus, who poses the theological question (with the fear of God in his eyes, I might add): “Do you believe, Marcus? Do you believe the Grail actually exists?”

Indeed, along with an exploration of Indy’s relationship with his father, Last Crusade is largely a test of Indy’s faith — or at least his capacity for it. Seriously, watching these three movies, you have to wonder how Indy remains a skeptic as long as he does in the face of columns of fire, melting Nazis, burning stones and miraculous healings. Midway through Last Crusade, though, we see Indy really start to doubt his doubt when, while being sucked toward the giant spinning blade of a cargo ship, a religious soldier says to Indy, “My soul is prepared [for death]. How’s yours?” True, Indy wasn’t ready to die just yet — he still hadn’t found his father — but Ford rightfully shows us the doubt in Indy’s eyes.

Obviously, a recap of Indy’s leap-of-faith moment should go here, it being the clearest display of an Indy who, with a bullet lodged in his father’s stomach, places a hand on his heart, closes his eyes, prays then takes a literal leap of faith.

How-ever, the image I find far more striking is the look in Indy’s eyes when he uses the Grail to heal his father. It’s his closest encounter with divinity. Yes, he touches the Ark, he touches the Sankara stones, but the Grail he touches while it is working its magic, while it is healing his father. The Sankara stones glow and catch fire, but Indy only gets to see them as a weapon, not as the benevolent force that the village mystic says they are. The same goes for the Ark, which, as we all know, turns into a ghostly porn star (“It’s beautiful!”) and then into a skeletal Nazi death bomb. Indy’s smile when he watches the Grail work its magic draws a benevolent parallel with an earlier moment in the film, when he discovers the entombed remains of a Grail knight. In both cases, Indy, his brow glittering with sweat, smiles in wide-eyed wonder, but when he smiles at his father, he’s smiling as a man of newfound faith, as opposed to his reaction at finding the Grail knight, where he’s smiling as an excited scientist, yes, but he’s also grinning in pure fortune-and-glory greed mode.

And fortune and glory now lead us into a look at Indy’s change from cold, greedy mercenary to the respectful historian who believes all artifacts “belong in a museum!” Here’s where the trilogy’s chronological sequence serves Indy’s character arc best: TOD, Raiders, Last Crusade.

Nice try, Lao Che!

OK, as far as Indy the mercenary goes, my argument begins with two words: flaming kebob. Indy slings a flaming kebob, javelin-style, into the chest of a Chinese gangster at the beginning of TOD. Yes, yes, yes — I know he’s been poisoned and needs to create a diversion but Christ! This is go-for-broke Indy; an Indy who would sell the cremated remains of a Chinese emperor for a big fucking diamond. This is an Indy who, when a half-dead, emaciated kid staggers into town with a scrap of parchment in his hand, shuffles the kid off to his mother so he can greedily leer at the fortune and glory in his hands. Going back to Indy the atheist: when Short Round asks Indy what the Sankara stones are, does Indy tell Short Round the legend of how Shiva gave Sankara the stones to fight evil? Nope, all he says is, “Fortune and glory, kid. Fortune and glory” (though he does relate the legend later).

But Indy’s paternal instincts, honed by his relationship with Short Round, lead Indy to give up the Sankara stones in favor of helping the small village whose children were kidnapped by Mola Ram and his Thugee assholes. “Ah, they’d just wind up collecting dust in some museum,” Indy says at the end.

By the time Raiders rolls around and the U.S. government commissions him to find the Ark, Indy’s first concern is for the museum, and at the movie’s end, Indy shrugs off his undoubtedly huge payday because of his concern over what the hell the government plans to do with the Ark. “The money’s fine. The situation is entirely unacceptable,” he says, later adding, “They don’t know what they’ve got there.”

This brings us to Jeffrey Boam’s Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.

OK, don’t get me wrong. Like I said before, Boam does a lot right in this movie. But he commits a few cardinal sins in my mind. First, the ignorant motherfucking jagoff apparently watched Raiders, like, once, saw that Indy wanted to give the Ark to a museum — and based on that one line turns Indy into a square-jawed doofus who twice during the first reel yells, “That belongs in a museum!” This wouldn’t be such a bad thing — I am arguing that by this point in the series Indy has become an upstanding archaeologist — but fuckbrain that Boam is, he has Indy say the same thing in the opening sequence, when Indy (well played by River Phoenix) is a Boy Scout!

Before I explain why this is such a lousy choice, let me concede that while I feel secure in blaming Boam for the movie’s summer-movie one-liners, the blame for larger character choices like this — making Indy a true-blue hero even as a youngster — must be divided evenly among Spielberg, Lucas and Boam, because not only are Lucas and Spielberg the primary story- and character-generators for the Indiana Jones movies, but they have both proven themselves to be overpowering personalities prone to crappy, crowd-pleasing cop-outs like making Indy a true-blue hero even as a youngster.

First let me vociferously concede how fucking awesome it is to see Indy as a kid. Holy shit. Total goodness. And what a treat it is to see another actor play Indy in a situation where it’s not some half-ass, Julianne Moore-as-Clarice-Starling recasting mess. And River Phoenix just drills this one. He makes the young Henry Jones Jr. his own while echoing Ford’s immortal performance at the same time. Fuck! Why did Phoenix have to die?! Not only did he get to play Chirs Chambers in Stand By Me, not only did he get to play Carl in Sneakers, but he got to play Indiana Jones! Fuck!

Anyway, the Spielberg/Lucas/Boam triumvirate screws up by making Indy into a true-blue hero in the opening sequence. Yes, by 1938 (when Last Crusade takes place), Indy the adult has put his flaming-kebob-throwing days behind him, but when he’s a kid no way. The triumvirate makes Indy the teenager smart and adventurous, but they should have made him greedy and mischievous, too. When Indy sees the Cross of Coronado at the beginning, his eyes should gleam with the same greedy glow we see so many other times in the movies (when he first sees the Ark or the Sankara stones, for example). Remember, he was accused of being a grave robber rather than an archaeologist, and the Sultan of Madagascar threatened to cut off his nards. Instead, the triumvirate blunts Indy’s character arc by resorting to a cheap joke.

(The only time we get to see the mischievous side of young Indy is when his father orders him to count to 20 in Greek as a disciplinary measure. If you listen closely, I’m damn sure he skips from five to 20 as he slides out the door with a sly grin. Well done, guys!)

Which brings me to my full-on new-asshole-tearing of Jeffrey Boam, Hollywood screenwriter. Now, while all three Indiana Jones movies were summer releases, Last Crusade, unfortunately, has the most summer-movie trappings — that is, dumb fucking summer movie jokes. Don’t get me wrong, I like a good laugh as much as the next guy, but what hurts the gags in Last Crusade is their cheapness.

Some of the worst offenses:

• After Indy guns down some Nazis (always cool), he quips, “Don’t call me junior!”

• “No ticket!” (A perfectly fine gag, but they wimped out by having Indy say it in English. It would have been much funnier if he had said it in German and they had trusted the audience to figure it out.)

• Sallah and Marcus Brody as buffoons, instead of the cool, kick-ass characters we see in Raiders. Yes, they both have nice moments in Last Crusade, but as a friend of mine once said, “The Sallah of Last Crusade wouldn’t have known the dates were bad.”

• And the piece de resistance: Indy’s fighting with some Nazis atop a tank. A periscope comes up. Indy’s crotch somehow gets shoved into the periscope’s eye. Inside the tank, we see a, shall we say, well-groomed Nazi smiling at the sight. Moments later, this suspect-looking Nazi says in a mincing voice (and I got this translation from a native German), “These Americans, they fight like sluts.” ARGH! Besides the glaring historical inaccuracy (an openly gay man? In the German army? During WWII? Uh, “master race,” anyone? Pink triangles and concentration camps, anyone?), I detest how Spielberg, Lucas and Boam resort to the “gay people are funny!” school of lame-ass, low-brow, sophomoric humor.

That said, Last Crusade does wrap up Indy’s journey to the light side of archaeology nicely. Despite the fact that he ditches out on his office hours, Indy has become a much better teacher, drawing as many laughs from his class as doe-eyed looks from the coeds. He does, indeed, turn over the Cross of Coronado to the lucky-as-hell museum he works for but we see Indy’s true respect for his craft when he meets the 700-year-old knight who guards the Holy Grail.

What a great scene. You know Spielberg’s a genius, right? I mean, how do you sell a scene where someone meets a 700-year-old knight and make it so quiet, moving and just plain cool? It takes great directing and pure commitment from your actors — and Ford plays this scene with just the right mix of reverence and bewilderment. I don’t know if the Indy from Club Obi-Wan would have had it in him to make that leap of faith. I don’t know if Indy the Honduran grave-robber would have had it in him to chug water from the Grail so willingly, or to listen to his father when that last vestige of mercenary greed — “I can almost reach it!” — manifests itself as he reaches for the Grail one last time.

Let’s see if moron-boy can get back to his thesis

So now: parenthood — a key theme in TOD and the key theme that unites TOD and Last Crusade, even though they take place four years apart from each other. Because I’m feeling guilty for lambasting Jeffrey Boam so much (and because I want to segue into my defense of TOD), let me praise Boam’s exploration of Indy’s relationship with his father in Last Crusade, specifically the scene on the motorcycle at the crossroads. This scene is a gem. I’d trade 10 action sequences for another scene like this. Consider this exchange:

INDY

This is an obsession, dad. I never understood it. Never. And neither did mom.

INDY’S FATHER

Oh, yes, she did. Only too well. Unfortunately. She kept her illness from me –

until all I could do was mourn her.

Wonderful. As opposed to all the other ham-handed, dipshit gags in this movie, here Boam writes realistic dialogue that tells us so much by telling us virtually nothing. What do these two lines mean? Presumably this is Indy’s father admitting that he ignored his wife in favor of his research, but how did that affect him? Or his son? I would think that Indy would be less likely to follow his father’s career path after watching it kill his mother, but he didn’t. Maybe he wants to make his father proud. Maybe he’s competing with him. Who knows?

In any case, I encourage you to watch the second and third Indiana Jones movies back-to-back, but in reverse order: Last Crusade and then TOD. And when you do, pay attention to the differences, not the similarities, but the differences between how Henry Jones Sr. treats his son and how Indy treats Short Round. Henry Jones Sr. is commanding, dismissive and impatient with his son, even slapping him in the face at one point “for blasphemy.” In short, Indy’s dad treats his son like a kid. By contrast Indy treats Short Round like an equal. Hell, even though Indy could probably go to jail for bringing Short Round along on his adventures, he treats him like a colleague. Yes, Indy calls him “shorty” and pats him on the head a few times, but he never, ever talks down to him. Man, when they’re playing cards and they start swearing at each other in Chinese? Classic! One quiet example of Indy’s respect for Short Round: When the village mystic says that a great evil has again risen in Pangot Palace, Short Round pokes Indy’s shoulder and says, “You listen to me, you live longer,” and Indy, unlike so many parents who would shut their kids up with a few harsh words, simply raises a finger for silence, just like he would with a fellow professor. Moreover, witness the implicit trust between Indy and Short Round, not only when Short Round’s driving the getaway car at the beginning of TOD, but also near the end, when Indy tells Short Round his plan to cut down the rope bridge they’re trapped on, once again in Chinese.

But at the same time, Indy is still Short Round’s dad. Consider the scene when they’re approaching Pangot Palace and Indy discovers a demented altar to Kalee that’s covered in blood and severed fingers. Short Round asks, “Doctor Jones, what you look at?”

And Indy, with paternal urgency and sternness in his voice, says, “Don’t come up here.”

Indy also apparently has spoken pretty frankly with Short Round about his sex life, based on how Short Round asks Indy to tell him what he does with Willie (Kate Capshaw) the night they spend in Pangot Palace; to say nothing of Short Round’s admonishment at the beginning: “Hey, Doctor Jones, no time for love!”

I’m not suggesting that all parents should tell their kids about the birds and the bees when they’re eight years old and take them on death-defying adventures. But I do believe in treating anyone — regardless of age or mental capacity — as equals, and that goes double for parents to their children. Treat your children like adults, and treat child-rearing as a series of wonderful challenges just like Indy does. Indy treats Short Round the way he wishes his own father had treated him.

Way back at the beginning of this essay, I said that TOD goes to a dark, scary and different place to explore the theme of parenthood. Detractors of TOD complain about this movie’s dark tone and freakshow divergence from the more familiar territory of the other two movies, which both involve Judeo-Christian treasures, a desert setting and lots of Nazis.

Well, here’s the deal: TOD tops Last Crusade because except for Sean Connery, Crusade is too much of a rehash of the first movie; and TOD tops Raiders because it’s different, because it turns Indy into a psychopath, because it ignores the structure of the other two movies. Man, I love how Raiders opens in the jungle and TOD opens with a Busby Berkeley number — something Spielberg confesses he had always wanted to direct — and as much as I enjoy seeing young Indy in Last Crusade, I admire how Spielberg and Lucas fearlessly stuffed as much old-time entertainment into their second Indiana Jones movie, regardless of what their audience wanted or was expecting.

And as great as Raiders is, Pauline Kael was on to something when she called it cold and impersonal. Indy mostly stays aloof from his friends (Marcus, Marian and Sallah) in Raiders. He treats Marcus like a silly old man and later tries to sweet-talk Marian in Nepal. Indeed, one of the few honest moments we get from Indy in Raiders comes only after Marian cold-cocks him (“I never meant to hurt you,” he says), but he backs away from his apology seconds later: “You knew what you were doing.” We only really get the idea that Indy’s a great guy from how Sallah speaks of him to Capt. Katanga: “These are my friends. They are my family. I would hear of it if they are not treated well.”

Again, the main criticism levied at TOD is that it’s too dark and scary (this coming after a movie that featured an exploding head). And while those critics have a point, watching Short Round claw, scratch and fight to save Indy’s life is the heart of the movie. Growing up, I can’t think of a more frightening device in fiction than an adult or parental figure going crazy or being abusive. The father in Radio Flyer. The terrifying psychologists in Return to Oz. King Haggard in The Last Unicorn. Hell, I still don’t like it when Kris Kringle acts like an asshole in Miracle on 34th Street.

Fighting for your father

Countless times through the other Indiana Jones movies we fear for Indy’s life, but only in TOD do we fear for his soul. The scariest image in the entire trilogy isn’t a ghost or a monster or a Nazi but the deranged void in Indy’s eyes when he’s brainwashed. And my heart still breaks when I watch Indy backhand Short Round. As difficult as the scene is to watch — still to this day — I commend Spielberg and Lucas for committing to this most horrific of images: a parent abusing their child. Because that’s what it is. Yes, they use the fantastic (a brainwashing serum) to produce the image, but it remains the same: A father (Indiana Jones) strikes his son (Short Round).

I’ve argued in this essay that Indy transforms from a kebob-slinging mercenary into a respectful professor. He becomes a warmer person, a person of faith. And while I don’t think faith is necessary to be a good person, perhaps in Indy’s case, he needed it. In any event, Indy’s rise from the muck of grave-robbing and money-grubbing starts when Short Round rams a flaming torch into his side and pulls him out of the Thugee’s waking nightmare. Indy hits bottom when he hits Short Round, and he knows it. I task you to find a harder-hitting or more heartfelt moment than when Short Round rears back with that fucking torch and says, “Indy, I love you!” That is what movies are all about. I’ve always admired Luke Skywalker’s unswerving love for his fallen father, but Short Round beats Luke by a longshot. And what does Indy do the second he wakes up? He teams up with Short Round to kick some ass, says he’s sorry – and then he goes to rescue the enslaved village children.

Hold on to your fedoras: If Mola Ram hadn’t brainwashed Indy and given Short Round the impetus to save him, I don’t think Indy would have freed the village children. Yes, Indy shows some empathy near the beginning when the village mystic tells him about the disappearance of the children, but I don’t think Indy had it in him. Not yet. Not with so much fortune and glory within his grasp.

Short Round helps Indy find his heart and soul. What do Raiders and Last Crusade have that can top that?